Embedded GPU Demand Risks Revealed Under ASC 842

A deep-dive into two material, yet underappreciated risks facing Nvidia and CoreWeave

Abstract

Nvidia’s valuation continues to hinge on robust investor sentiment over the AI spending environment as it forges new all-time highs. But a critical oversight may be superficially skewing market expectations. The following analysis will examine the underappreciated implications of ASC 842 Lease Accounting, which yields two material risks to Nvidia’s growth and valuation outlook. First, it highlights how hyperscaler capex – a key barometer of Nvidia demand – is increasingly tied not only to long-term leases on structural components like office buildings and data centers, but also GPUs. This dynamic raises embedded risks of double-counting AI GPU demand, and underscores a potential overstatement of $11 billion in Nvidia’s anticipated data center sales for FY 2026 alone. Second, the analysis examines fundamental vulnerabilities in CoreWeave’s GPU depreciation and capex strategy. It’ll dive into finance lease dynamics observed across its key hyperscaler customers – particularly, Microsoft. The findings corroborate escalated risks of imminent asset impairment, which Nvidia is exposed to given its 7% stake in CoreWeave.

Introduction

Hyperscaler capex spend has been a key focus area in recent years, as it serves as a critical gauge for impending AI infrastructure commitments – and, most importantly, a direct barometer for Nvidia’s demand outlook. The growing influence of AI-related capex trends on both valuation and market sentiment was evident earlier this year, when training efficiency revelations from DeepSeek spooked investors about potential spending fatigue in the industry. At the time, markets witnessed Nvidia losing 17% of its value in a single day, wiping out about $590 billion from its market cap to mark the worst intra-day decline since March 2020. Subsequent headlines about Microsoft potentially pulling out of planned data center leases only further amplified market anxiety. It wasn’t until the U.S. “Big 4” hyperscalers (i.e., Microsoft, Google, Amazon and Meta Platforms) reaffirmed their full-year AI spending commitments during the March quarter earnings season that assuaged investor fears.

While strong headline capex commitment from the Big 4 U.S. hyperscalers have fueled optimism around Nvidia’s growth trajectory, there has been relatively limited scrutiny into how much of that spending really flows directly to chipmakers. And this isn’t merely about the allocation between AI processors vs. other long-lived assets (e.g., fulfilment facilities and equipment, office buildings, data center colocations, etc.), or merchant GPUs vs. custom ASICs, or even Nvidia vs. its competing rivals.

What remains largely overlooked is the distinction between capex allocated to direct hardware purchases vs. leases. Specifically, the implications of ASC 842 Lease Accounting warrant greater attention, given rising relevance of long-term leases amid surging AI infrastructure investments and the emergence of the GPU rental market.

As evidenced in neo-cloud operator CoreWeave’s sustained rally since its IPO earlier this year and management’s emphasis on surging demand for its core GPU rental business, the capital deployment landscape is rapidly evolving. Long-term leases are no longer a nominal component in hyperscaler capex commitments that’ve historically been tied to structural components of operations like office buildings, data center colocation facilities, and/or equipment. Instead, they now represent a strategic avenue for accessing high-value AI infrastructure, particularly GPUs, critical to industry growth roadmaps.

This shift has accordingly levied material implications for how hyperscaler capex should be interpreted moving forward – both in terms of spend visibility and its direct impact on AI technology enablers like Nvidia. In this context, understanding ASC 842 Lease Accounting is no longer optional. Only through a clear grasp of how finance leases are reported under ASC 842 can investors accurately assess Nvidia’s near-term monetization potential and avoid overestimating demand embedded in headline capex figures.

In the following analysis:

I’ll begin with a brief primer on ASC 842 Lease Accounting.

I’ll then proceed with a two-part analysis that reveals two underappreciated, yet imminent and material risks to Nvidia’s growth outlook that stem from these accounting implications:

1) The overstatement in growth expectations currently underpinning Nvidia’s rally to all-time highs; and

2) The growing mismatch between hyperscaler GPU rental demand and CoreWeave’s expansion plans – a dynamic that poses indirect risks to Nvidia, given its role as a strategic investor in the neo-cloud operator.

What is ASC 842 Lease Accounting?

ASC 842 Leases is the U.S. GAAP standard employed by many reporting participants across the AI value chain today, including the Big 4 U.S. hyperscalers, Nvidia, and CoreWeave. The guidance provides oversight on leases of all long-lived assets (e.g., PP&E), including the differentiation between short- and long-term leases, and how each type is to be accounted for in financial reporting.

Short-Term Leases

Under ASC 842, a short-term lease is defined as “a lease that has a lease term of 12 months or less and does not include a purchase option that the lessee is reasonably certain to exercise”. For instance, if an enterprise customer goes to a neo-cloud operator like CoreWeave or Nebius, and rents a couple of hours of H100 capacity under a 1-month contract, then it’s a short-term lease.

Long-Term Leases

**The following may be quite confusing for the day-to-day investor. If you’re not interested, and just want to know enough to understand the imminent risks facing Nvidia and CoreWeave, then here’s the condensed version:

There are two types of long-term leases: 1) finance lease, and 2) operating lease. A finance lease would represent a lease where the lessee assumes ownership of the underlying asset; the contract value over the lease term is equal to or exceeds the fair value of the underlying asset; and/or the lease term is for the major part of the remaining economic life of the underlying asset. For instance, if a hyperscaler rents GPU capacity from a neo-cloud operator for five years out of the six-year remaining useful life designated for the underlying GPU, then the arrangement would be classified as a finance lease.

Alternatively, any long-term lease exceeding 12 months that does not exhibit any of the aforementioned characteristics would be classified as an operating lease. For instance, if a hyperscaler rents GPU capacity from a neo-cloud operator for two out of the six-year remaining useful life designated for the underlying GPU, and the total lease payment only represents the minority of the underlying GPU’s fair value, then the arrangement would be classified as an operating lease.**

Now the real deal on classification, initial measurement and subsequent accounting for long-term leases is detailed as follows:

Under ASC 842, long-term leases are defined as any lease that has a lease term of more than 12 months. There are two types of classifications for long-term leases:

Finance lease: Any long-term lease with a lease term of more than 12 months and exhibits one or more of the following characteristics:

o The lease transfers ownership of the underlying asset to the lessee

o The lease includes an option for the lessee to purchase the underlying asset that the lessee is reasonably certain to exercise

o The lease term is for the major part of the remaining economic life of the underlying asset

o The present value of the sum of lease payments over the lease term and any residual value guaranteed by the lessee is equal to or exceeds substantially all of the fair value of the underlying asset

o The underlying asset is specially curated for the lessee and has no alternative use to the lessor

Operating lease: Any long-term lease with a lease term of more than 12 months that does not exhibit any of the criteria required for finance lease accounting.

Every lessee will need to perform a classification assessment of the lease as of commencement date, as that would dictate the subsequent accounting and financial reporting disclosures for the arrangement.

Regardless of whether the long-term lease is classified as a finance or operating lease, the underlying asset involved would be considered a “right-of-use” – or “ROU” – asset with a matching lease liability that’s recorded on the lessee’s balance sheet.

The lease liability recorded at lease commencement should reflect the present value of total lease payments over the lease term. And the ROU asset recorded at lease commencement would represent the total of the initial measurement of the lease liability; any additional amounts made to the lessor related to the lease at or before the commencement date, net of lease incentives; and any indirect costs incurred by the lessee (e.g., commissions). If there are no additional amounts made to the lessor at lease commencement and no indirect costs involved, then the ROU asset should match the lease liability at initial measurement and reporting on the lessee’s balance sheet.

The subsequent wind-off of lease liability and ROU asset amortization is as follows:

ROU asset: Amortized using the straight-line method over the shorter of the useful life of the asset or the lease term. For instance, if an enterprise customer enters into a long-term operating or finance lease for GPU capacity from a hyperscaler or neo-cloud over a two-year lease term, but the underlying GPU asset has a remaining useful life of six years, then the enterprise customers will amortize the ROU asset over two years.

Lease liability: The lease liability is reduced annually based on the difference between the annual lease payment and the annual interest expense accrued on the total lease liability outstanding. This means the lease liability reduction will be smaller during the earlier years of the lease term (due to greater interest accrued) and increase over time.

It’s the subsequent impact on the income statement that differs between finance lease and operating lease accounting:

Finance lease: An annual interest expense accrued on the outstanding lease liability is recorded on the income statement. Because the outstanding lease liability is greater during the earlier years of the lease term, the annual interest expense impact on the income statement is also accordingly greater. This results in a frontloaded cost impact on the income statement for finance leases, which declines over time.

Operating lease: In contrast, operating lease expense on the income statement is recorded on a straight-line basis over the lease term. If the annual lease payment is $10,000, then the same amount will be recorded as an operating lease expense on the income statement. Although the accrued interest is still considered in the annual lease liability wind-off exercise, it’s not separately reported on the income statement.

Part I: Market Estimates for Nvidia GPU Demand are Overstated

During Nvidia’s Q4 FY 2025 earnings call, CFO Colette Kress disclosed that the U.S.’ largest hyperscalers now account for more than half of the company’s data center revenue, with CEO Jensen Huang adding that demand stemming from the cohort has primarily been driven by internal consumption needs:

“In Q4, large CSPs represented about half of our data center revenue…And the CSPs have internal consumption and external consumption, as you say. And we are using – of course, used for internal consumption.” - Nvidia Q4 FY 2025 Earnings Call

This has accordingly made capex guidance from the Big 4 U.S. hyperscalers a key barometer for Nvidia’s forward demand. To date, Microsoft, Google, Amazon and Meta have collectively announced more than $310 billion of capex for the current year, with potential for further increase towards more than $330 billion in 2026. The bulk have been attributable to AI infrastructure buildouts, including servers equipped with Nvidia GPUs.

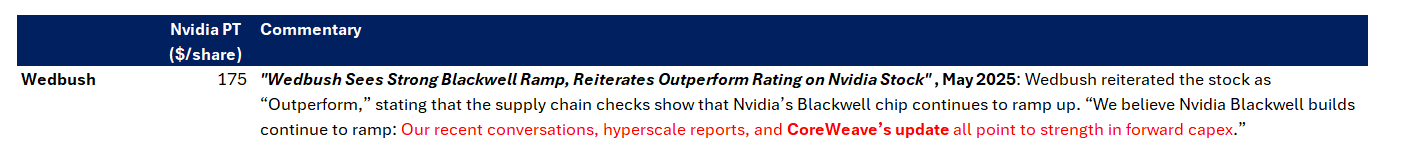

These figures have also become key inputs in Nvidia’s growth forecasts and stock price projections among top Wall Street analysts:

Yet based on the compilation of institutional equity analyst projections and analyses, none have really paid close attention to amounts attributable to finance leases, which are commonly disclosed by management as part of their capex outlook.

As discussed in the above crash course on ASC 842 lease accounting, a finance lease relates to one where the lessee – or hyperscaler, in this case – essentially assumes ownership of the underlying asset. This is achieved either by committed use of the underlying asset over the majority of its remaining useful life or by extracting the majority of the underlying asset’s value over the lease term. As much as 20% of hyperscaler capex commitments in 2024 have been attributable to finance leases, up from 15% in 2023. Total finance lease capex incurred by the U.S. Big 4 hyperscalers in 2024 have increased by 27% from the prior year:

The consistent increase in finance lease capex aligns with hyperscalers’ aggressive expansion of their data center and colocation footprint in recent years to facilitate burgeoning AI demand. In addition to related land and building leases, another key contributor to the increase in finance lease capex is GPU rentals – an emerging corner in the AI value chain that’s only gained relevance in the last two years.

The GPU rental market is currently dominated by hyperscalers themselves, as well as a niche cohort of neo-cloud operators, including CoreWeave and Nebius. CoreWeave generated close to $1 billion in revenue during Q1 2025 alone – four times higher than the same quarter last year and already accounting for nearly half of its total $1.9 billion revenue from all of 2024. Nebius showed similar momentum, with Q1 2025 sales up four-fold y/y, also representing about half of its 2024 revenue. Hyperscalers have been key demand drivers for the GPU rental market, as the lease-based model grants them access to immediate deployment, flexibility and cost efficiencies.

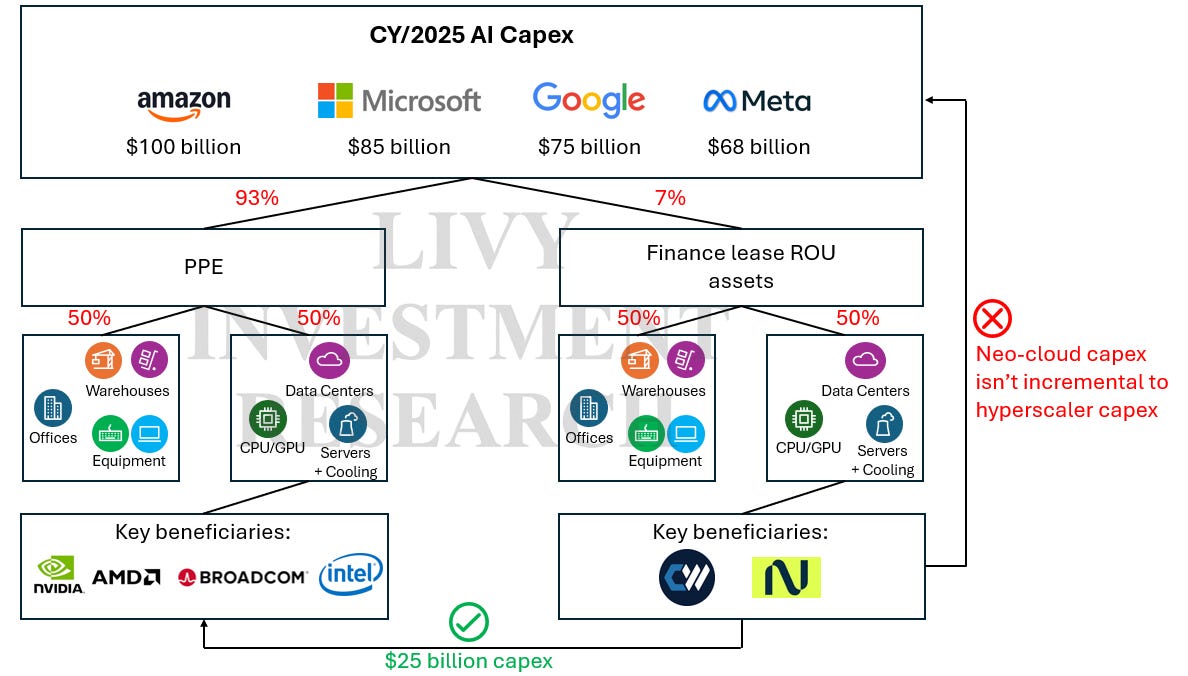

This explosive growth underscores the rising relevance of GPU rentals – and consequently, finance leases – in accelerating AI infrastructure deployment. Based on recent observations, it can be safely assumed that at least 7% of planned 2025 and 2026 capex amongst the U.S.’ largest hyperscalers will be represented by finance lease arrangements, with about half linked to GPU rentals. That’s $11 billion in 2025 AI capex that will not go directly to merchant GPU purchases from Nvidia, but rather to neo-cloud providers like CoreWeave and Nebius instead.

And here’s the issue: In addition to capex from the U.S. Big 4 hyperscalers, markets are increasingly baking in spending from neo-cloud providers to support a more bullish outlook for Nvidia’s growth. This is reflected in analyst AI capex estimates for 2025 and 2026, which consistently exceed the guidance provided by the Big 4 alone. The overshoot suggests markets are factoring in incremental demand from other sources – such as other cloud-service providers like Oracle, enterprise and sovereign buyers, and neo-cloud operators like CoreWeave and Nebius.

Wedbush, for example, is one of the analysts that’ve expressed incremental optimism tied specifically to CoreWeave’s capex on top of what the U.S. Big 4 hyperscalers have committed to in inferring Nvidia’s strong demand outlook:

But what’s really happening is that markets are at risk of overstating Nvidia’s demand outlook by double-counting finance lease GPU commitments. As noted earlier, about $11 billion of the U.S. Big 4 hyperscalers’ planned capex is expected to be fulfilled through GPU rentals instead of direct purchases. That demand will ultimately flow through to Nvidia via neo-cloud providers like CoreWeave and Nebius, which have collectively planned $25 billion in 2025 capex.

As a result, AI hardware demand that Nvidia’s poised to benefit from would be the $310 billion from hyperscalers – and not an inflated sum that’s inclusive of neo-cloud operators’ $25 billion of planned capex spend.

Considering Nvidia is currently trading at 19x NTM sales, with markets at risk of mistakenly pricing in $11 billion in overstated GPU demand, the stock is potentially overvalued by $210 billion – or more than 5% of its market cap – today. Or to put into better perspective, a third of Nvidia’s $620 billion rally this year is likely attributable to overstated revenue expectations.

The broader impact on sentiment could pose an even greater headwind. A similar dynamic was evidenced in mid-April, when Nvidia shares dropped nearly 14% during the week that followed the U.S. government’s announcement of export curbs on the H20 GPU to China, alongside management’s subsequent disclosure of a related $5.5 billion write-off. While applying a 19x multiple to the write-off would imply a $105 billion impact, the sharper selloff likely reflected a broader market re-rating around Nvidia’s longer-term growth curve, which was lowered as a result of weakened penetration propsects into China AI opportunities.

A comparable correction could follow once markets fully recognize the extent to which current growth expectations priced into Nvidia’s valuation are overstated. The adjustment likely wouldn’t stop at the $11 billion overstatement estimated for the current year. Instead, it’d likely have a compounding effect by lowering Nvidia’s multi-year growth curve and, inadvertently, its valuation multiple as well.

More importantly, signs of intensifying competition are also emerging based on the consistent decline in hyperscaler capex (ex-finance leases) as a percentage of Nvidia data center revenue in recent years.

This observation potentially implies diversion of spend to competitors and/or other AI infrastructure components (e.g., software, server racks and infrastructure, etc.). For instance, Google has recently been giving greater focus on revenue-linked investments according to management’s commentary during the Q1 2025 earnings call, which infers increasing GPU deployments:

“And as you've seen in the comment I've just made on cloud, we do have demand that exceeds our available capacity, so we'll be working hard to address that and make sure we bring more capacity online.” - Google Q1 2025 Earnings Call

Yet the consistent decline in Google’s capex (ex-finance leases) as a percentage of Nvidia’s data center revenue suggests the GPU install mix is increasingly being diverted to rivals – like Broadcom, given Google’s heightened focus on its in-house developed TPU. This would also be consistent with Google’s increasingly vertically integrated strategy:

“We also look at every investment that we make to ensure that we're doing it in the most cost-efficient way to optimize our data center. As you know, our strategy is mostly to rely on our own self-design and build data centers. So they're industry-leading in terms of both cost and power efficiency at scale. We have our own customized TPUs. They're customized for our own workload. So, they do deliver outstanding superior performance and CapEx efficiency.” - Google Q4 2024 Earnings Call

Taken together, Nvidia’s all-time high valuation today appears to be priced for more than perfection. And it has certainly yet to de-risk for double-counting in estimates due to market’s continued underappreciation for the finance lease component of hyperscaler capex. This is further compounded by the growing diversion of related investments toward Nvidia’s rivals instead.

Part II: Mismatch in GPU Lease Demand vs. CoreWeave Capex and Depreciation Schedule

There’s also been much debate on whether CoreWeave has employed appropriate accounting on the valuation of its long-lived assets – particularly, the GPUs currently underpinning its core business model. The discrepancy between the six-year useful life CoreWeave has attributed to its GPUs versus the much shorter span employed by comparable peer Nebius, alongside the accelerating decline in GPU rental rates due to the rapid cadence of tech advancements has raised causes for caution.

Nebius has specifically disclosed in its 2024 Form 20-F that its GPU assets are depreciated using the straight-line method over a four-year useful life. And during its Q1 2025 earnings call, management had provided updated clarification that the company now uses a “full year depreciation schedule” for its GPU assets. While it’s unclear whether this suggests the newly acquired GPUs are fully depreciated within one year, or if they retain a four-year useful life but are depreciated in full during the year of purchase rather than pro-rated, either case implies a much shorter useful life than what CoreWeave’s employed. Even at the most generous estimate, Nebius is likely depreciating its GPU assets over an average of about three years. This would align with Nebius’ evenly distributed quarterly capex. In Q1 2025, the company spent $544 million in capex, just over a quarter of its $2 billion full-year guidance. This suggests roughly half of its planned GPU purchases would be back-end loaded, but subject to full-year depreciation, leaving about three years of remaining useful life.

As I’ve explained before, “useful life” is a strictly defined term in GAAP. The Accounting Standards Codification employed by U.S. GAAP defines useful life as “the period over which an asset is expected to contribute directly or indirectly to future cash flows” – or the period over which the asset is expected to generate an economic value to the business.

This means CoreWeave’s assignment of a six-year useful life to its GPU assets implies an expectation that the hardware will not only remain operational over that period, but also continue to generate economic value for the company throughout. But here’s the problem – Nvidia has recently committed to a one-year advancement cadence to its product roadmap. This has effectively accelerated the pace of hardware obsolescence, leading to a rapid decline in the price and rental rate of past-generation GPUs. With everyone demanding the latest and greatest, which promises better performance and TCO, rental rates on past-generation GPUs like the H100 have dropped significantly from its peak. In early June, Amazon disclosed it has slashed rental prices on older generations of Nvidia GPUs by as much as 45%:

CoreWeave itself, and peer Nebius, are also currently offering H100 rentals at as low as $2 per hour, which is a whopping 75% drop from peak prices at about $8 per hour two years ago, and 23% drop from just a little under a year ago. This accordingly highlights the adverse shift in business unit economics for CoreWeave, which raises doubt on whether its currently extended GPU depreciation schedule is appropriate.

With GPU rental rates facing a steepening decline as new advancements get introduced to market at a rapid pace, CoreWeave now faces a tighter timeline to breakeven. If a GPU investment made today isn’t fully recoverable within two years of the designated six-year useful life, then it’s poised for impairment given limited demand and price accretion expected in the remaining four years. U.S. GAAP currently requires reporting companies to assess the asset useful life and recoverable value annually for impairment. If the total recoverable amount of the asset is expected to fall below its cost recorded at initial measurement, then the difference will need to be written off from the balance sheet with an impairment expense.

This is a very real and material risk for CoreWeave that’s being underappreciated by markets, as evidenced in the stock’s continued upsurge to new all-time highs.

In CoreWeave’s latest earnings call, management sought to assuage these concerns by clarifying the company employs a “success-based” capex strategy, whereby investments are only deployed when there’s sufficient contracted revenue to ensure breakeven within the GPU’s useful life:

“Our capital expenditures are success based. Substantially, we enter into compute CapEx programs when we sign multiyear contracted revenue that more than covers the cost of the CapEx within the contract terms. This enables us to responsibly scale our debt structures that support this contractual revenue and utilize naturally deleveraging self-amortizing debt facilities that allow for us to maintain a relatively low leverage multiples.” - CoreWeave Q1 2025 Earnings Call

But the only way to mitigate CoreWeave from asset impairment risk is if the contracted revenue are linked to the specific GPU in which it seeks to invest in today. With CoreWeave planning $23 billion in capex this year, which will likely be fully deployed towards procuring Nvidia’s Blackwell systems, the corresponding contracted revenues would need to be directly linked to those chips to justify the investment.

However, if $23 billion in new long-term contracts are signed this year and realizable over six years – but transferrable to newer, more advanced GPUs – then the recoverable value of today’s Blackwell-related capex faces inevitable impairment risk. This is due to the anticipated rental rate haemorrhage once Blackwell passes its two-year peak cycle, making it increasingly difficult for revenue from the remaining four years of useful life to contribute towards recovering initial deployment costs.

This is likely the case facing CoreWeave. It’s just not economically viable for any of its customers – especially not Microsoft, its largest customer – to make such a sizable long-term commitment to one GPU series when they face imminent obsolescence within two years. Doing so would be akin to knowingly committing to an onerous contract at risk of lease asset impairment – not to mention the active breach of fiduciary duty to investors.

So, you may ask – how is ASC 842 lease accounting relevant?

CoreWeave has disclosed in its S-1 and latest Q1 2025 10Q filings that Microsoft remains its largest customer. As of March 31, 2025, Microsoft contributed to 72% of CoreWeave’s revenues. This illustrates a consistent uptrend from 35% in the year ended December 31, 2023, and 62% in 2024. Since Microsoft contributes to the majority of CoreWeave’s revenues, a quick check into its lease accounting dynamics would reveal whether CoreWeave’s success-based capex strategy is sustainable – and whether the six-year useful life attributed to its GPU assets is valid.

Remember, finance leases represent long-term lease contracts that exhibit essence of ownership assumption – either by encompassing a lease term that spans over the majority of the underlying asset’s remaining useful life or by encompassing a total lease payment value that is equal to or exceeds the fair value of the underlying asset. For instance, if Microsoft commitments to Blackwell capacity from CoreWeave for five of the chip’s designated six-year useful life, or if the committed rental payments are equal to or exceed the system’s underlying fair value today, then it’d be accounted for as a finance lease. This would be accordingly reflected on Microsoft’s balance sheet as a finance lease ROU asset typically embedded within its PP&E balance, with a matching finance lease liability typically embedded within other current and long-term liabilities.

As mentioned earlier, it’s unlikely Microsoft would want to commit to six years of Blackwell rental capacity today. However, Microsoft may be incentivized to enter into a shorter-term, high-value rental contract with CoreWeave that covers the entirety of Blackwell’s current fair value in order to offset some of its near-term supply shortfall from Nvidia. As such, it’s worth examining how much Microsoft’s finance lease ROU assets have changed in the past year to estimate the scale of GPUs it has effectively “acquired” through rentals – and how that compares to CoreWeave’s planned capex for 2025.

Based on Microsoft’s FY 2024 10K, the amount of finance lease ROU assets embedded within its PP&E balance was $25,862 million as of June 30, 2024, up 63% y/y compared to the muted 13% y/y increase observed in FY 2023. The disclosure specifies that its operating and finance leases are primarily related to “data centers, corporate offices, research and development facilities, Microsoft Experience Centers, and certain equipment”. The substantial increase in finance lease ROU assets in FY 2024 is likely inclusive of GPU rentals and data center leases, given Microsoft’s heightened focus on AI infrastructure buildout in recent years:

“Cloud and AI related spend represents nearly all of total capital expenditures. Within that, roughly half is for infrastructure needs where we continue to build and lease data centers that will support monetization over the next 15 years and beyond. The remaining cloud and AI related spend is primarily for servers, both CPUs and GPUs, to serve customers based on demand signals.” - Microsoft Q4 FY 2024 Earnings Call

This is also corroborated by management’s brief commentary during the Q4 FY 2024 earnings call on expectations of a greater mix of finance lease capex going forward to support the ongoing AI infrastructure build-out:

“The other thing, I would note, Kash, is you'll also notice there's a growing distinction between our CapEx number, and on occasion, the cash that we pay for PP&E and you're going to start to see that more often in this period because it happens when we use leases. Leases sort of show up all at once. And so you'll see a little bit more volatility.” - Microsoft Q4 FY 2024 Earnings Call

Finance lease ROU assets have continued to increase through year-to-date FY 2025. As of the nine months ended March 31, 2025, Microsoft included $37,625 million of finance lease ROU assets within its PP&E balance. That’s an increase of $11,763 million in the nine months since fiscal 2024 year-end. Hypothetically, consider half of the $11.8 billion of new finance lease ROU asset additions at Microsoft are fully attributable to server GPUs, and all of it goes to CoreWeave. That would still only amount to about 26% of CoreWeave’s planned $23 billion capex for 2025 – which deviates significantly from management’s confident confirmation that the amounts to be deployed are backed by sufficient long-term contracts to ensure breakeven.

Now, let’s consider a more aggressive scenario:

Microsoft currently anticipates about $80 billion of total capex in FY 2025 – likely on the way to finish the year at $85 billion. Based on the amount attributable to finance leases observed through Q3 FY 2025, which averages about 26% of quarterly capex, it’s likely Microsoft will add about $22 billion of finance lease ROU assets this year. By applying the same assumption to Microsoft’s FY 2026 capex, which is estimated at more than $90 billion given management’s expectations for capital spending to increase over the next year, its finance lease ROU asset additions would likely reach $24 billion in the next 12 months:

Management has also disclosed during Microsoft’s Q4 FY 2024 earnings call that half of capex is primarily attributable to servers – including both CPUs and GPUs. Half of the anticipated finance lease ROU asset addition for FY 2025 would represent $11 billion. Hypothetically, even if all of it goes towards CoreWeave GPUs, it’d still be a significant shortfall from the $23 billion in capex that the neo-cloud operator’s prepared to deploy this year. In other words, only a little under half of CoreWeave’s $23 billion GPU investments this year are secured by a breakeven contract from Microsoft at best.

Arguably, CoreWeave must’ve forged long-term lease contracts with other hyperscaler customers as well. This is supported by the consistent increase in operating lease ROU asset additions – or long-term lease contracts that don’t make up the majority useful life and/or value of the underlying asset – across hyperscalers in recent years:

While operating leases would only account for limited parts of a GPU’s useful life and value, they could potentially add up across hyperscalers to help CoreWeave breakeven on the asset. But here’s the issue – Microsoft currently accounts for 72% of CoreWeave’s revenues, with the metric consistently growing.

This means all of CoreWeave’s other customers combined currently represent less than a quarter of its revenue. And based on disclosures within CoreWeave’s latest Q1 2025 10Q, no other individual customer accounts for more than 10% of its revenue, further challenging the economic viability of its planned $23 billion capex spend this year.

As a result, it’s highly unlikely that the rest of CoreWeave’s customer base – generating just about 25% of its revenue – can deliver sufficient accretion to ensure the recoverability of $23 billion worth of 2025 GPU investments over the next six years. This would be consistent with Microsoft’s modest finance lease commitments attributable to server GPUs, implying limited incentive to lock-in long-term on third-party facilitated hardware that’s bound to become obsolete within two years. It’s further corroborated by the dominant portion of capex earmarked towards direct PP&E purchases observed across hyperscalers, highlighting their preference for full ownership of GPU assets instead to scale both external and internal workloads over the longer-term.

Although CoreWeave’s recently secured an $11.9 billion five-year contract and $4 billion four-year contract with OpenAI, there’s also no guarantee they’re tied specifically to Blackwell deployments either. The hesitation would be consistent with the rapid pace of LLM advancements observed at OpenAI, which likely coincides with preference for the latest and greatest hardware that’s currently improving at a “one-year rhythm” according to Nvidia. This accordingly weakens prospects of recoverability for CoreWeave’s $23 billion capex this year further.

The totality of facts considered would imply that as much as half of CoreWeave’s $23 billion in planned GPU investments this year are at risk of partial impairment, with the ensuing write-off estimated at $6 billion.

There just isn’t sufficient evidence drawn from hyperscaler and enterprise lease commitments that CoreWeave’s $23 billion GPU investments planned for this year can be fully recouped over a six-year useful life nor within the next two years to dodge obsolescence. Although management doesn’t typically talk about this, it’s a big enough threat to be included in the company’s latest “Business and Industry” risk disclosures within the Q1 2025 10Q:

Taken together, it’s evident CoreWeave’s six-year depreciation schedule and success-based capex strategy is not durable nor appropriate for its business model. Any subsequent impairment, which CoreWeave’s prone to, would impact its earnings outlook – something that the stock’s current valuation premium leaves no room for.

More importantly, the adverse dynamic would also subject CoreWeave to heightened liquidity risk. The company’s success-based capex strategy is primarily upheld by leverage due to CoreWeave’s ballooning losses and lack of self-sufficiency in funding operations today. Although management has painted CoreWeave’s business model as “invest first, then scale” and recover over the average asset useful life cycle of six years, that doesn’t seem to be the real-world case based on long-term lease dynamics observed across its core hyperscaler customers. Most recently, CoreWeave’s raised $2 billion in a senior notes offering at 9.25% due 2030. Yet that’s barely a drop in the bucket based on the incremental debt required to sustain its so-called “success-based” capex strategy in the coming years.

As a result, the CoreWeave stock faces significant downside risks from current levels. In the event of a correction to adjust for its potentially overstated GPU asset values, Nvidia would also be exposed due to its 7% stake in CoreWeave. It would also be detrimental to current investor confidence over the forward AI infrastructure spending trajectory – something that Nvidia’s $4 trillion market cap leaves no room for.

Conclusion

ASC 842 lease accounting has become more relevant than ever before in the tech industry. Not only because it’s embedded in hyperscaler capex forecasts – a figure that investors have been obsessed with – but also due to its increasing relevance in evolving dynamics across the AI value chain. Historically, the finance lease component of hyperscaler capex has primarily been related to data center, corporate office and other equipment rentals. But rapid AI infrastructure buildout has also exposed finance lease relevance to an emerging corner of GPU rentals. This has accordingly increased finance lease’s significance in gauging growth prospects of key picks-and-shovel players like Nvidia and CoreWeave.

But it’s likely market hasn’t quite grasped the concept, as evidenced by Wall Street estimates that take the entirety of both hyperscaler and neo-cloud capex into inferring Nvidia’s growth outlook. Although these numbers imply strong demand for AI GPUs, it doesn’t mean the fundamental underpinnings of Nvidia’s valuation aren’t overstated due to double-counting.

ASC 842 lease accounting has also revealed cracks in CoreWeave’s capex strategy and depreciation cycle. While it’s easy to be distracted by CoreWeave’s multi-fold growth, current lease dynamics observed across its key hyperscaler customers suggest the company’s business model is inherently prone to impairment. This would imply an impending accounting-related valuation reset at CoreWeave. And Nvidia wouldn’t be off the hook either, given exposure via its 7% stake in CoreWeave.

It’s evident both implications learned from lease accounting – something that most tech investors do not pay attention to – yields two material headwinds to Nvidia that its valuation today has yet to de-risk for. Be informed, and don’t be caught off guard.

Disclaimer: This analysis is for informational purposes only and represents the opinions of Livy Research. It is not investment advice nor a recommendation to buy or sell the securities discussed.